The French and Indian War, pt. 2: A Lake Between Two Empires

- Timothy Dusablon

- Jul 18, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Aug 2, 2025

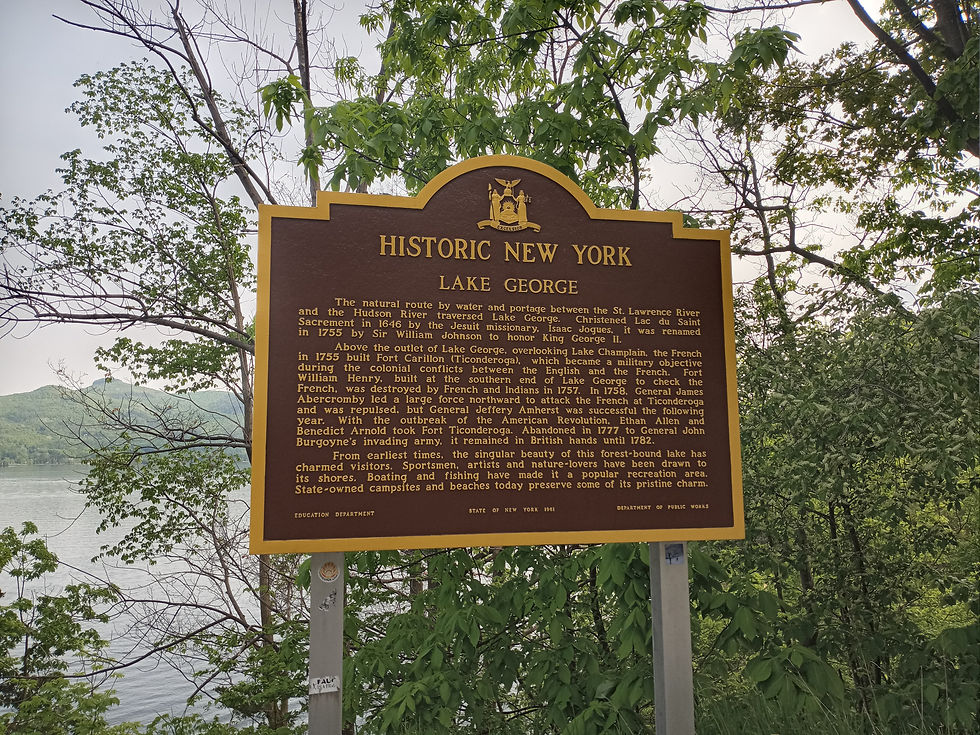

As the calendar turned to 1756, a lake emerged as the boundary between two empires in what many call the first world war. Lake George became a desolate war zone, with only scouting parties going north or south. For the next four years, Lake George became the front lines in the battle between empires.

Up to this point on previous episodes, many of the events take place on Lake Champlain. For the next few episodes, our focus shifts to the magnificent Lake George. This magnificent lake, thirty two miles long and over 200 feet deep in some locations, became the focus of kings thousands of miles away.

It’s sadly ironic that a place of such natural beauty and tranquility would see such horrific warfare. From one end of Lake George to the other, and a few placed in between, iconic battles that still live in infamy amongst famed European regiments unfolded. Once again, we see why this region is truly the crossroads of a continent.

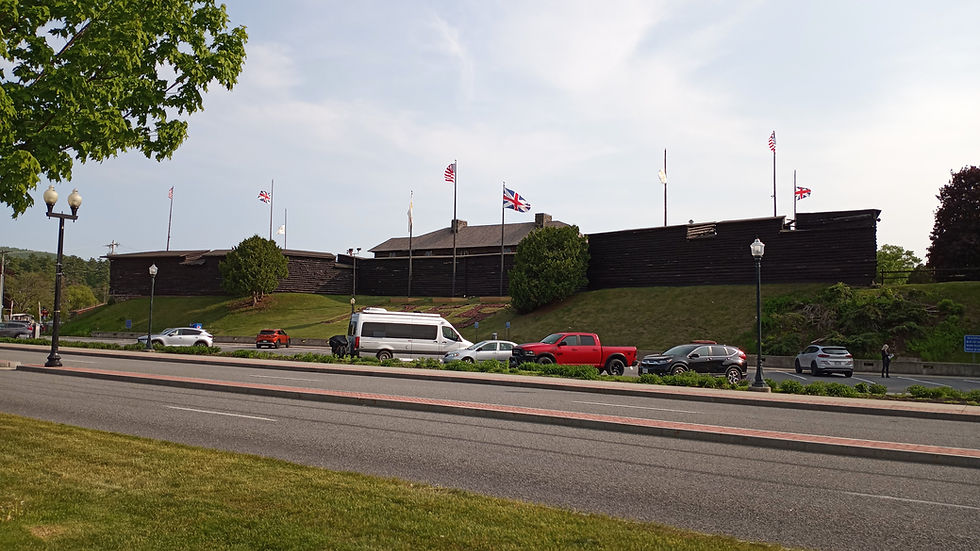

At the southern end of Lake George, Immediately after William Johnson’s victory at Lake George, the forces built a small wooden stockade fort. However, Johson and William Eyre urged the colonies to approve construction of a larger earthen and timber fortification. It was eventually approved. Construction began for Fort William Henry. The wooden fort only lasted two years, and the events that brought the end of the fort would be one of the defining moments of the French and Indian War. It would even inspire a historical fiction novel and several hollywood adaptations titled, “The Last of the Mohicans.”

Fort William Henry

Fort William Henry gave the British a direct path to the French-controlled Lake Champlain, and the forts along its shore. If they were able to get past those forts, they had a direct water route to the heart of New France along the St. Lawrence River. The fort would also be a hindrance for any French force looking to proceed to Albany, and would be able to be garrisoned during the winter months to prevent raids like the Schenectady raids in the previous wars.

Design and construction of Fort William Henry was overseen by Captain William Eyre. a young New Englander named Jeduthan Baldwin assisted him with the construction, and learned the fundamentals of military defensive-works. Unbeknownst to Captain Eyre, he was training the future enemy of Great Britain. During the Revolutionary War, Baldwin designed the fortifications at Mount Independence, directly across Lake Champlain, on the Vermont side, from Fort Ticonderoga.

Fort Carillon (Ticonderoga)

Speaking of Fort Ticonderoga, at the northern end of Lake George, where the waters from the lake empty into Lake Champlain via the La Chute River, construction was underway on a French fort that would also become famous. This fort was made famous by an improbable French victory, as well as the role the fort would play in forming a country that did not yet exist. That fort was Fort Carillon, which eventually became known as Fort Ticonderoga.

Very few fortifications in North America can match the history of Fort Carillon, or Ticonderoga. During its rather short existence as a functional fortification, Ticonderoga saw six different occasions when an enemy approached the fort. Amazingly, four out of those six attempts resulted in the capture of the fort. Just three years after its construction, the Battle of Carillon took place in 1758. This battle was the bloodiest battle on American soil prior to the Civil War with close to 3,000 casualties. More about this in part four of the French and Indian war episodes. In 1775, a group of colonial rebels seized Ticonderoga more than a year before the Declaration of Independence had been signed. The capture of the fort by Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold was the first major victory for America, and provided much needed heavy artillery for George Washington in Boston. In 1777, John Burgoyne recaptured the fort for the British, exploiting the failure of the American forces to fortify nearby Mount Defiance, which is in direct range of cannon to the fort. The celebration for Burgoyne was short-lived though, as he would surrender his large British and German force about three months later at Saratoga, the turning point of the Revolutionary War.

To build Fort Carillon, Governor General Vaudreuil looked to Michel-Chartier de Lotbiniere. Assessing the Carillon (Ticonderoga) peninsula, he found a rocky outcropping with cliffs nearby. Lotbiniere used oak timbers spaced about ten feet apart and filled with earth. Initially, Fort Carillon, or Ticonderoga, was built with timber. The officers quarters inside the fort were built with limestone. However, the French eventually reinforced the timber with stone, giving the fort a similar look to the reconstruction we see today. The reconstruction wisely used stone only, as the wood would no doubt have rotted out and caused structural issues as it did during the Revolutionary War.

Just to the south of the fort, a site called the French village emerged. This site was surrounded by a stockade of logs and included kilns, a blacksmith, bread ovens, and other structures. Lotbiniere has been accused of using this venture to enrich himself, as he had exclusive rights to selling wine to the crew building the fortification. In addition to the fort at the top of the rocky outcropping, a redoubt was built on the shore of Lake Champlain to further hinder the potential movement of the British. This was called Lotbiniere’s redoubt. A sawmill was built by the French at the lower falls of the La Chute River. In addition, three outposts were built along the La Chute River as well as the northern tip of Lake George, near Mossy Point.

The British had planned on a renewed offensive against Fort St. Frederic and Fort Carillon in 1756. A contingent of colonial soldiers again from New York and New England had gathered at Fort Edward, as planned by Braddock’s successor, the Governor of Massachusetts, William Shirley. The force failed to move forward, owing to a lack of supplies and concerning reports of the size of the French force currently constructing Fort Carillon. Then, sudden leadership changes changed plans on both sides.

Leadership Changes

Continued attacks against Shirley (many from William Johnson himself) had caused leaders in London to make a change in command. John Campbell, the Earl of Loudoun, was placed as the new commander of forces in North America. His second and third in command were Major Generals James Abercrombie and Daniel Webb. Both men’s reputations would be ruined due to future events in the Champlain Valley in 1757 and 1758 respectively.

On the French side, the replacement for the Baron de Dieskau, who was wounded and captured in the Battle of Lake George, was Louis Joseph, Marquis de Montcalm. He was much more of a traditionalist when it came to warfare, and disliked the irregular “petit guerre”, or woodland warfare, that had dominated North American conflict in the century prior. On paper, he was to report to the Governor General of New France, Pierre de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnial. The salty Montcalm would have none of this, and dismissed Vaudreuil’s insistence on using First Nations Warriors to attack the English. The rivalry that emerged between Vaudreuil and Montcalm came to define the French war plans until Montcalm successfully lobbied the decision-makers in Paris to give him complete control in 1758. Vaudreuil viewed Montcalm as arrogant and brash, and Montcalm viewed Vaudreuil as an incompetent micro-manager.

Montcalm visited Fort Carillon in July 1756 before returning to Montreal to lead an offensive against Fort Oswego with 3.000 French regulars, Canadian militia, and 250 First Nations Warriors. Montcalm and his force made quick work of the British defending Fort Oswego, to the surprising disappointment of General Montcalm. His goal was for the offensive to last long enough to divert men from Fort Edward and Fort William Henry so that another offensive could take place on Lake George. However, given the disappointing defense of Fort Oswego, that plan had been foiled.

The aftermath of this battle raised concerns amongst the British. In what became a dress rehearsal for what was to happen at Fort William Henry in the following year, the natives took to plundering the fortification for the spoils of war, proof of their valor in battle that they could bring back to their nations. As the fort was opened, the warriors plundered, and chaos soon erupted to Montcalm’s chagrin. Several of the British were killed, and 1,700 were taken prisoner by the natives. Montcalm, greatly concerned about what this would do to his reputation as a gentleman and a General, paid top dollar back in Canada for these captives. Word spread about the amount of goods and money exchanged for these prisoners amongst the First Nations. This reputation would play a major role in the “massacre” at Fort William Henry in 1757. News of this concerning development spread to Fort Edward just as Montcalm made his way to Fort Carillon, causing great concern amongst the colonials.

Robert Rogers and the Rangers

Much of the intelligence officials had at Fort Edward and Fort William Henry was due in large part to a New Hampshire regiment led by a man named Robert Rogers. This regiment would grow to many more, and his abilities at irregular warfare gave his unit the name of Rogers Rangers. This was a light infantry unit. They were essentially the special ops unit of the French and Indian War.

Robert Rogers is one of the most polarizing figures in the history of the Champlain Valley. Some historians, especially Francis Parkman, view him as a shining example of the enterprising American spirit on the colonial frontier - a man who was unafraid of the most daring military actions of the French and Indian War. Other, more recent historians have a far less favorable viewpoint. They view Rogers as a shameless self-promoter who often exaggerated his own reports and as such is greatly overrated.

Rogers was indeed brave, and never showed cowardice in the face of danger. He had an incredible ability to escape from scenarios that seemed almost impossible to escape from. He was also an incredible leader, who’s men admired and trusted him. He also had a dark side, and battled his demons with alcohol and gambling. His family farm in New Hampshire had been destroyed by an Abenaki raiding party when he was a child. This led to a deep-seeded hatred for the Abenaki, and fueled his desire for vengeance during the St. Francis Raid in 1759.

What can’t be denied is that Robert Rogers took ranging warfare to a new level amongst the British Forces during the French and Indian War. It was here, along the shores of Lake George and Lake Champlain, that Robert Rogers created the “Rules of Ranging”, a guide still in use today amongst American ranger companies. He was a badly needed counter to the woodland warfare tactics of the French and their native allies. Rogers led several raids against French settlements, killing civilians and destroying personal property, much like the raids the French had excelled at against the colonies since 1690.

Several prominent figures were members of Rogers Rangers. Amongst those were future American Revolutionary War figures Israel Putnam and John Stark. Also among this group was Noah Grant, the Great-Grandfather of Ulysses S. Grant.

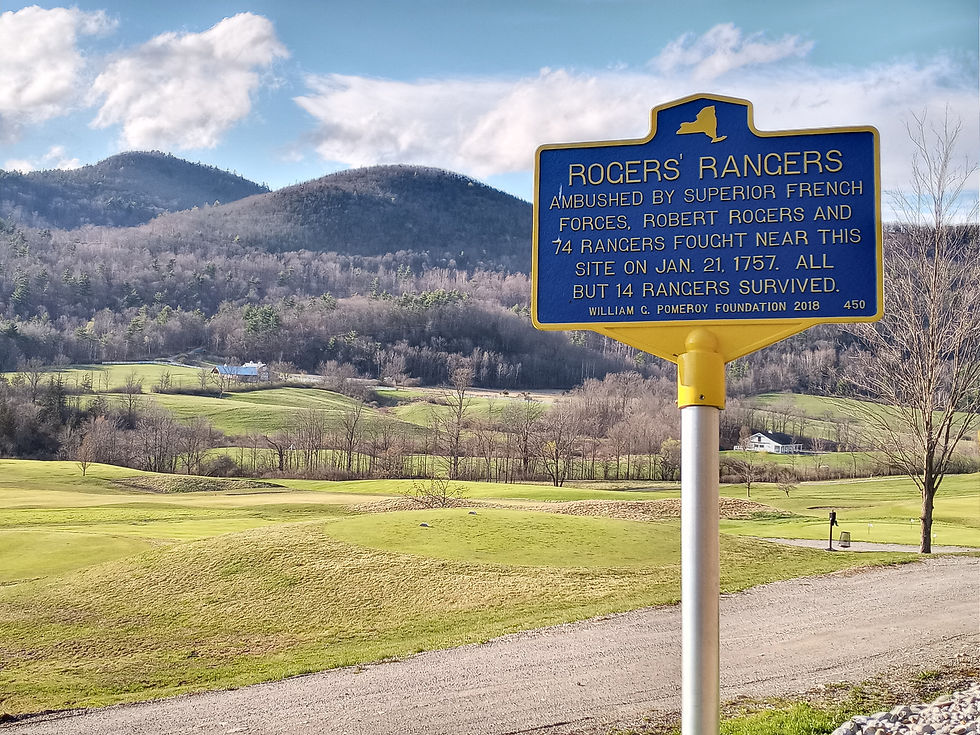

First Battle on Snowshoes 1757

During January of 1757, Rogers and 70 rangers set out from Fort Edward to the French forts on Lake Champlain in an effort to harass the works as best they could. On the western side of the frozen Lake Champlain, halfway between Fort St. Frederic and Fort Carillon, Rogers spotted a horse drawn sleigh proceeding along the icy surface. Rogers sent out Lieutenant John Stark, the future Revolutionary War hero, to intercept the sleigh. As Stark moved forward, Rogers spotted several more sleighs just up the lake. He tried to send the message to Stark to wait for the other sleighs before ambushing, but it was too late. 5 sleighs went back to Fort Carillon, and sounded the alarm.

Learning the strength of the French and First Nations Warriors at the two forts, Rogers ordered a retreat along the same path they took to Lake Champlain. This was a violation of one of Roger’s rules of ranging which states you are never supposed to go back by the same route.

The French sent a force from Fort Carillon of 160 men to intercept the retreating rangers. In a ravine, the French fired upon Rogers and his force, wounding Rogers himself twice and inflicting many casualties. The rangers were actually lucky that the casualties were not higher, as the damp, snowy conditions made many of the muskets on the French side inoperable. The Rangers returned the fire as best they could, and were able to hold out until nightfall. At this point, it was determined that the rangers make their way back to Lake George and Fort William Henry as soon as possible. Rogers and his rangers had the advantage of having snowshoes on, and were able to create distance with the French force following them. This would be known as the first Battle of Snowshoes.

Winter Raid on Fort William Henry

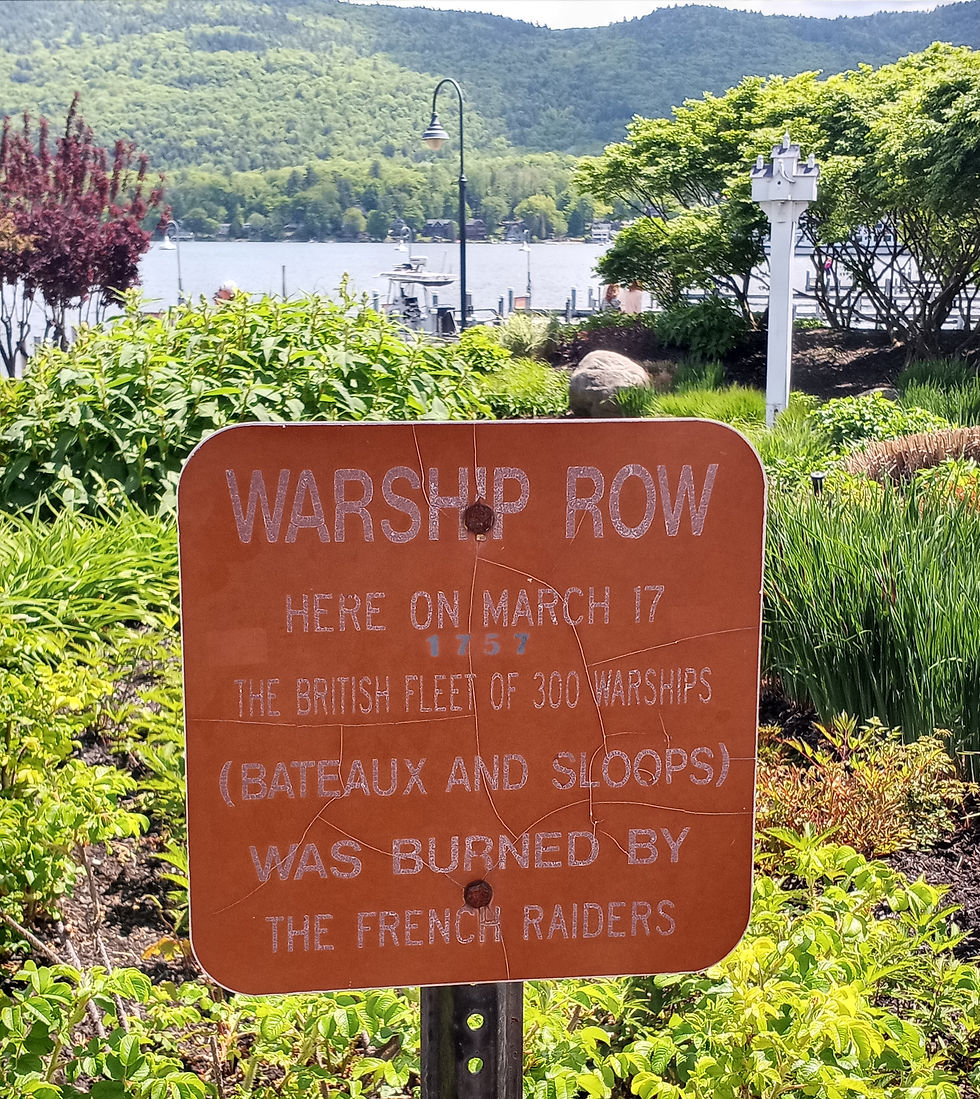

Two months later, Governor Vaudreuil ordered a daring wintertime raid south along a frozen Lake George to Fort William Henry. Commanding this raid would be his brother, Francois-Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil. A force of 1,600 men left on March 15th and crossed the frozen lake, equipped with scaling ladders in hopes of capturing the fort. They arrived near Fort William Henry on March 19th. Had they arrived two days earlier, they would have found many of the British regulars of Irish descent drunk off of rum, in celebration of St. Patrick’s Day.

The French force going south on Lake George had encountered awful conditions for marching. A spring thaw had melted some of the snow and ice on the lake’s surface. They were trudging through 6 inches of standing water on top of the ice of tenuous thickness. Proceeding at night, the head of the French forces used lanterns and hatchets, continually testing the thickness of the ice.

At 2am, the fort was put on high alert, as a noise was heard as well as a light spotted out a distance on Lake George. Shortly after, still during nightfall, the assault began. The defenders of the fort were able to repel the French forces with cannon fire, shelling the attackers with grapeshot. For five days, the siege continued, mostly at night. Colder weather and snow had returned, refreezing the lake surface and creating miserable conditions. Scaling ladders were brought forward, and Vaudreuil offered surrender terms under a flag of truce. Vaudreuil had warned that if the fighting continued, he would not be able to contain the “cruelties” of the First Nations Warriors in a foreshadowing of what was to come later that year. Captain Eyre declined the offer, and stated he would defend the fort to the last.

The French retreated back to Carillon in large part due to heavy snows that had hindered their offensive. They were unable to capture Fort William Henry. However, they did succeed in destroying almost every other building outside of the fort, including the naval vessels that were planned to move British forces up Lake George for an offensive in the spring. According to official French reports, this had been the objective all along, rather than the capitulation of Fort William Henry. Whether that was their true goal or not may never be known, as that was written after the fact. But the British now had only the fort, and no means to go on the offensive. The French planned to take advantage. The stage was set for the infamous siege of Fort William Henry.

This is part two of the French and Indian War series. For part one, click here. For part three, click here.

Sources:

Anderson, Fred. “Crucible of War: The Seven Years War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766”

Bellico, Russell P. “Empires in the Mountains: French and Indian War Campaigns and Forts in the Lake Champlain, Lake George, and Hudson River Corridor”

Brumwell, Stephen. “White Devil: A True Story of War, Savagery, and Vengeance in Colonial America”

Cohen, Eliot A. “Conquered Into Liberty: Two Centuries of Battles Along the Great Warpath That Made the American Way of War”

Eccles, W.J. “The French in North America 1500-1783”

Millard, James P. “Lake Passages: A Journey Through the Centuries Volume I 1609-1909”