The French and Indian War, pt. 4: An Improbable Victory - The Battle of Carillon

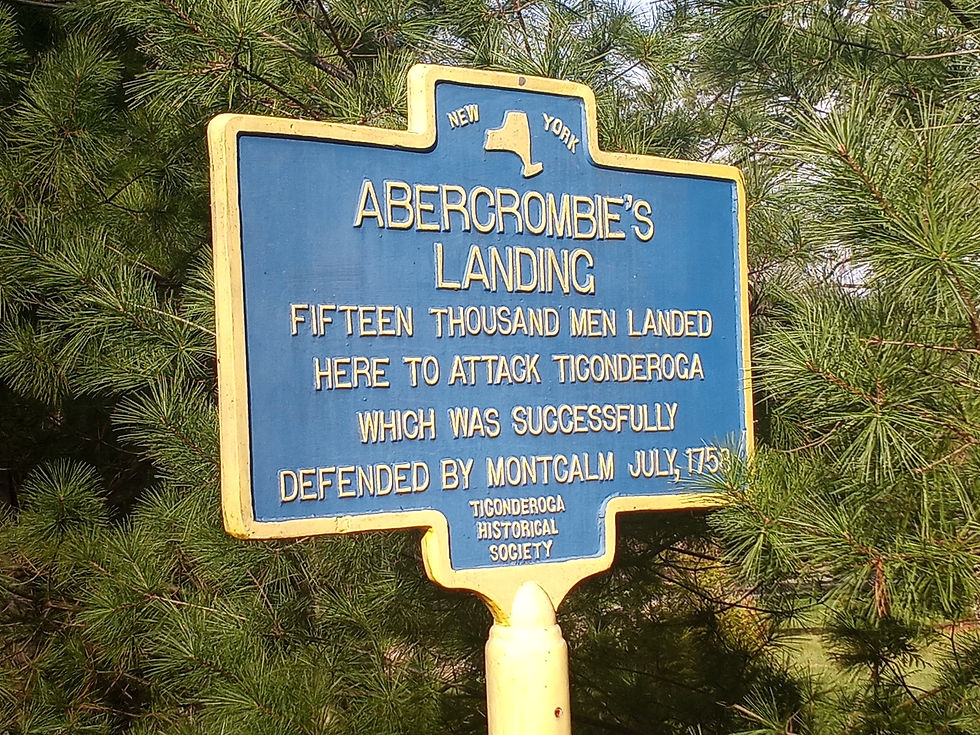

- Timothy Dusablon

- Aug 16, 2025

- 16 min read

Updated: Sep 6, 2025

Montcalm's Miracle

In 1758, the largest army ever assembled in North America up to that time, gathered on the ashes of Fort William Henry to avenge the "massacre" from the previous year. 17,000 British and Continental soldiers would move north along Lake George to attempt to capture Fort Carillon from a mere 3,500 French troops left to defend it.

This should have been a rout. This should have been over in hours. Instead what happened was one of the greatest upsets, and one of the greatest blunders, in North American military history. The Battle of Carillon would influence attitudes towards British military leadership for a generation of colonial fighters. In less than 20 years they would be taking on those they fought alongside in this battle. Fort Ticonderoga, which Fort Carillon was later named by the British, had a mythic reputation of impenetrability that carried over to the Revolutionary War. The Battle of Carillon was so influential to the French Canadians that the modern day Flag of Quebec was inspired by a flag believed to have flown during the legendary battle.

But what happened? How is it even possible that an army of 3,500 defeated an army 5 times their size? We will discuss in detail shortly.

But first, let’s look back on another important event that happened during the winter months in 1758 - the Second Battle of Snowshoes.

The Second Battle of Snowshoes

Robert Rogers and 183 men set off on a ranging mission from Fort Edward, heading to Fort Carillon. Reaching Lake George, the force marched on snowshoes mostly at night to avoid detection. At Sabbath Day Point, the site of the atrocities of Parker’s expedition the year before, they send a scouting group on skates up the lake. When they returned, they determined it wise to make the rest of the track on land, on the other side of the mountain range. This was done to protect them from the French advance posts at the northern end of Lake George.

At Fort Carillon, Abenaki scouts reported fresh tracks in the snow of the enemy believed to be 200 in number. Almost immediately, a force of 93 First Nations Warriors jumped at the chance for fighting, being bored of winter quarters at the fort. Following shortly after was a much more organized force under Canadian Officer Levreault de Langis.

At the other end, some of Roger’s advance scouts noted the initial force approaching their position. Rogers made a bet that the force would use the frozen creek bed to march south, and set up an ambush. Rogers was correct. They laid the perfect trap. When the native force was almost parallel with both sides of Rogers’ ambush, they opened fire. The force of First Nations Warriors were routed. The Rangers then split into two groups, one pursued the survivors, and the second force stayed behind to plunder and take scalps of the enemy.

But Rogers and the rangers did not realize that a much larger force of 205 men was following in the footsteps of the previous group. In the following engagement, the rangers lost 50 of their force almost instantly. A few tried to surrender, but the First Nations Warriors were not interested. They brought back just three English survivors as “living letters” to the French for further interrogation.

Following the rules of ranging, the force split up in all directions and retreated to a pre-designated rendezvous point. Rogers himself narrowly escaped, although how he escaped is up for debate. Local lore states that Rogers retreated to a granite cliff face over 700 feet tall over Lake George, and slid down to safety. Another version of the story states that Rogers put his snowshoes on backwards and marched from the cliff face to another easier spot to reach Lake George. This was reportedly done in order to misguide any would-be followers. Whether either of these legends is true is up for debate, as Rogers makes no mention of it in his journals. It seems though, that at very least the legend itself can be dated back to the 1760s. Several accounts and maps refer to the rock as “Rogers Slide” or “Rogers Leap.” This area is still known today as Rogers Rock.

Despite the lore that the Battle of Snowshoes receives, it was a debacle for Rogers. He lost over a hundred desperately needed rangers, over half of his force, despite inflicting heavy losses on the enemy.

A Turning Point in the War

But come the summer, plans were underway for the most daring and bold attack by the British up to this point. William Pitt had taken over for Lord Loudoun in command of British forces in North America. Whereas Loudoun wished to rule the North American colonies with an iron fist, much as Braddock did during his brief tenure in the position, Pitt wished to collaborate with the colonies. Gone were the bitter disputes with colonial governments as had been the case under Loudoun. William Pitt wished for a more collaborative approach to British interests on the continent. He offered generous terms for the use of provincial forces, and offered reimbursements for war expenditures that the colonies incurred.

This switch marked a major shift in colonial attitudes towards the conflict. Whereas before the attitudes were somewhat neutral, there now was a sense of renewed energy on behalf of the colonialists. The opinion shifted toward a shared victory over the French and their native allies.

Pitt planned a three pronged offensive in 1758. This time, he hand-picked the leaders of the missions. John Forbes would move against Fort Duquesne in the Ohio Valley. For the campaign against Louisbourg, he looked to Jeffrey Amherst, a smart and calculated leader. He would lead the campaign in the Champlain Valley the following year. Under Amherst was an impulsive and aggressive leader named James Wolfe. He would unleash sheer terror and a war of attrition in the St. Lawrence River Valley.

However, leading the campaign against Fort Carillon was James Abercromby. He was still in command, as had been the case under Loudoun, but Pitt did not hold him in high regard. He thought of Abercromby as indolent and lazy. And for reasons of seniority, he had to be in charge of this mission. For second in command however, Pitt looked to Lord George Augustus Viscount Howe to be the heart and soul of the mission. Pitt looked to Howe to provide the youth and vigor to the mission that Abercromby lacked. On top of this, by all accounts, Howe was a natural-born leader. Howe handled much of the logistical planning for this mission.

At the head of Lake George, the largest military force in North American history to that time had gathered. The total number of British regulars was 6,000. In addition, another 11,000 colonial troops took part. That brought the total English force to 17,000. Many of the colonials had been “paroled” by Montcalm the previous year at Fort William Henry. Abercromby, however, considered the agreement “null and void” after the “atrocities” that followed.

They rebuilt a stockade fort on the site of the old Fort William Henry, and proceeded forward. Morale was high, and Lord George Augustus Viscount Howe had boosted that morale. Even though he was born of an aristocrat, and was a Lord in the old country, he was loved and respected by all of the men, even by the colonial troops. This was in stark contrast to so many other British leaders from the old world. He dined without fancy silverware, slept on the ground with the other troops, and cleaned his own linens in the brook.

Most of all, he admired the new way of irregular war on the American frontier and wished to learn more. He spent a lot of time with Rogers and his Rangers, and accompanied them at the front of the flotilla making its way north on Lake George. To make a sports analogy, he was the player’s coach. The clubhouse leader. And, rightfully, should have been leading the expedition instead of Abercromby, but for reasons of seniority and politics, he would have to settle for second in command.

One Could not See Water

The force departed the head of Lake George on July 5th. This massive army proceeded north on Lake George with numbers so massive that French scouts could not see water in between the shorelines. The flotilla was 7 miles long and included 900 bateaux and 135 whaleboats.

On the next day, the forces landed at the northern end of the lake to find the French fortifications on Lake George and the La Chute River were abandoned. They had consolidated at Fort Carillon, where Montcalm had a force of only 3,500 men. A contingent of 1,600 troops under the Chevalier de Levis was sent on a diversionary force by Vaudreuil. This at a time when the fort absolutely could not spare that many men. Montcalm began to wonder if Vaudreuil, the Governor General of New France and his bitter enemy, was sabotaging him.

He sent a desperate plea for more reinforcements in addition to rations. They only had enough food on hand to feed the army for 9 days. This was due in large part to two straight years of failed harvests in Canada. Louis-Antoine de Bougainville called the situation “critical”. To make things worse, he had only 15 First Nations Warriors with him at Carillon. This is in stark contrast to the 1,500 he had just the year before in the fateful Fort William Henry expedition. This was the result of the alienation felt by many of those First Nations in the aftermath of the siege.

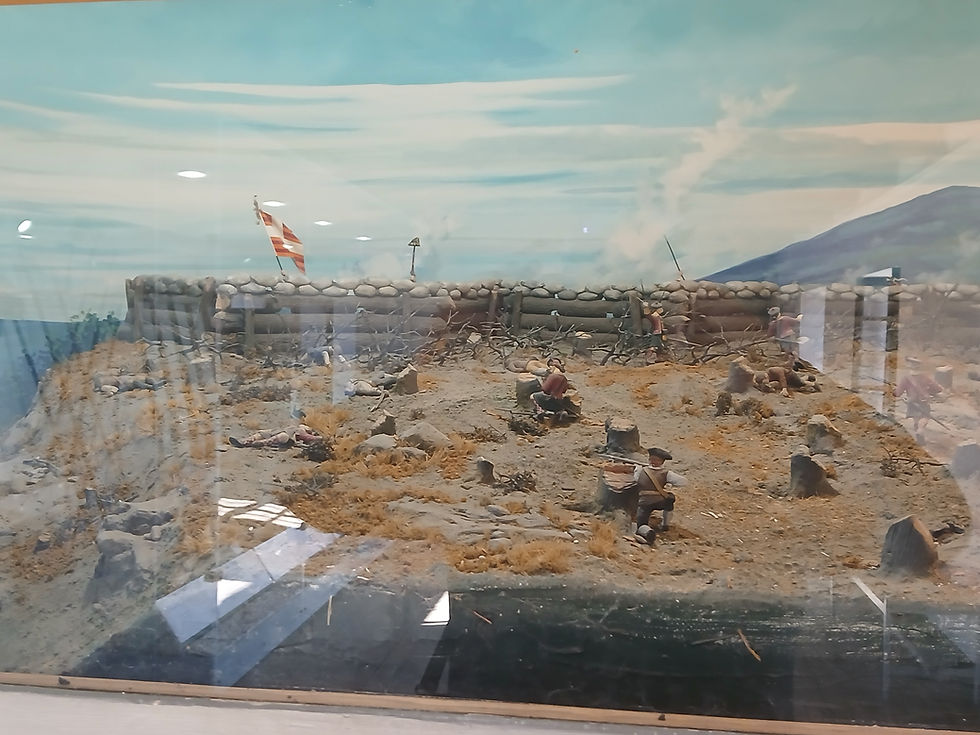

Montcalm faced the harsh reality that Fort Carillon would not be defendable against a force of 17,000. He gave thought to abandoning the fort and retreating to Canada, given that Fort St. Frederic at Crown Point was in far far worse shape. He instead decided on a huge gamble. One that ultimately paid off and showed brilliance. Instead of defending the fort, he improvised a wooden breastwork on the Heights of Carillon, the highground just to the northwest of the fort.

The Tragedy of Lord Howe

Back at the site of the British landing at the northern end of Lake George, disaster struck. While marching through the thick wilderness, an advance of the British army stumbled upon a French force, and a confusing skirmish took place. In terms of casualties, the French actually received the worst of this melee. But, in the skirmish, George Howe was shot through the chest and died immediately. The army was devastated by the news. The heart and soul of the mission was now gone. This was a crushing blow to the morale of the troops, and led to mass confusion amongst Abercromby and the remaining leadership. The army would not advance for two more days, confused and seemingly without direction. This would set in motion the debacle that followed.

Meanwhile, the French got busy. The French troops under General Montcalm, numbering just 3,500, set to work felling trees and sharpening branches to create an abatis. This mess and tangle of branches and sharpened wood extended about 100 yards to the woodline. The felled trees were the equivalent to the barbed wire similar to what we saw on the beaches of Normandy on D-Day. Similarly, the abatis, or branches sharpened to a point, were the equivalent to the Czech Hedgehogs that prevented tanks. Still, Montcalm had serious doubts about his chances at victory. He kept bateaux at the ready and was prepared to evacuate if the British brought heavy artillery to the front lines.

On July 7th, the day after Howe’s death, Abercromby moved forward only halfway to Fort Carillon, and paused to build trenches and a base of operations at the site of the French sawmill. This was at the lower falls of the La Chute River. He never sent scouts to spy on the French works until the following day, the day the offensive began.

Abercromby relied on a junior engineer to see the French works. He provided faulty intelligence stating that the French lines were weak, and could be knocked down with a stiff shoulder. John Stark, future American Revolutionary War hero at the Battle of Bennington, strongly disagreed and protested, stating the French lines were much stronger than they thought, but to no avail. From the vantage point of Sugar Loaf Hill (known as Mount Defiance today), the scout did not have a proper view of the defensive works, as the French had disguised them with shrubs. This would prove to be very costly.

With the fear of French reinforcements, which he believed were due at Carillon any day, and intelligence that the lines were weak, Abercromby decided to leave the heavy artillery at the shore of Lake George. He thought he would not need it, and that it might cause a costly delay with the approach of the rumored reinforcements.

These were all poor decisions from an indecisive leader. Even if the number of reinforcements that was rumored had come, the British would still have vastly outnumbered the French. They could have simply surrounded the fort and cut off supply lines, and gained victory without a shot being fired. As stated, the French only had enough food for a week. He could have brought the heavy artillery up to the front lines and blasted through the breastworks. He also could have employed flanking maneuvers around the front lines. Instead, he opted for a full frontal assault without heavy artillery.

"Mowed Down Like a Field of Corn"

The first wave moved forward. It was an absolute disaster. The French mowed down the oncoming British forces and inflicted heavy losses. A Massachusetts private stated they were “cut down like grass”. A British regular similarly stated they were “mowed down like a field of corn.” Abercromby decided to regroup, but instead of realizing the plan of a frontal assault was a failure and changing tactics, he sent another wave towards the French lines. Again, the French stood their ground and inflicted very heavy losses to the British.

For a brief moment, an elite group was able to penetrate the French lines through sheer bravery. These were the distinguished Scottish Highlanders, or the Black Watch as they were known. The famed Black Watch, which still exists today, has exemplified bravery dating back to the Jacobite Rebellion, through to World War I and II, and even played a major role in Iraq in 2003. Perhaps the darkest day of the famed Black Watch was July 8th, 1758. Of the 1,000 men of the Black Watch, 647 were killed or wounded. Among the killed was the famed Duncan Campbell, whose ghost story involving Ticonderoga is one of the greatest folklore tales of the Champlain Valley.

On the French side, the gunners at the front of the breastwork were continually handed loaded muskets. This created an almost never-ending barrage of fire. Montcalm was on the front lines with his men, doing everything he could to support the force. This was in stark contrast to Abercromby, who never visited the front lines and remained at his encampment over a mile away.

Abercromby sent a third wave, a fourth, a fifth, and a sixth, all with the same devastating and disastrous results. It was a horrific scene. The lack of direction and communication only added to the devastating scene on the battlefield. Counting the skirmish in which Howe lost his life, there were almost 3,000 casualties. This made the Battle of Carillon the bloodiest battle on American soil prior to the Civil War. That’s right, the bloodiest battle on American soil prior to the Civil War happened on the shores of Lake Champlain! So numerous were the casualties that 18 years later, during the Revolutionary War, American soldiers who were lacking in supplies used the thigh bones of the victims to make tents, and used their skulls as drinking vessels.

Montcalm's Cross

As daylight was coming to an end, the British retreated back to the northern end of Lake George in a panic. Meanwhile, the French celebrated their triumph. A large wooden cross was erected at the order of Montcalm, and he gave thanks to God for the defense of the fort. He ordered beer and wine brought to the men on the front lines. But they had to prepare for another raid the following day by the British. Or so Montcalm thought.

As daybreak came the following day, the French waited for the arrival of the British. And waited…and waited. They never came. Montcalm waited a day to send a spy, thinking that this surely was a ruse. He finally sent scouts to spy on the British at the northern end of Lake George. The scouts came back with the news that the British were gone, and were retreating back to the southern end of Lake George. They left in such haste that over 500 pairs of boots were still stuck in the mud. Montcalm was baffled, and so were the retreating British troops. William Johnson, the hero of the Battle of Lake George in 1755, tried to change Abercromby’s mind, but had no luck. Even despite the heavy casualties amongst the British troops, they still had an incredible numbers advantage over the French. The retreat was absolutely unthinkable, even after the heavy losses.

It was an absolute embarrassment for the British. An unrivaled debacle that almost fails to adhere to logic that a victory by the French was even conceivable.

Despite the tide of the larger French and Indian War shifting to the British in 1758, the French had an incredible moral victory, and Lake Champlain remained in French hands. This was the last great major victory for the French in the new world, that is until the Battle of Yorktown in the Revolutionary War.

This battle gave Fort Carillon, or Fort Ticonderoga, a reputation as an impenetrable fortress, a reputation that would carry over into the Revolutionary War. However, the condition of the fort during the Revolutionary War did not justify this reputation.

Back in Canada, the victory in the Battle of Carillon made the Marquis de Montcalm a hero. This despite Vaudreuil, his bitter rival, chastising him for not pursuing the enemy after their retreat. This is almost laughable considering how low Montcalm’s provisions were.

Legacy: The Flag of Quebec

The battle also influenced the modern day flag of Quebec. The story goes that Recollet Brother Louis-Francois Martinette rescued a flag from a fire in the Church of the Recollets in Quebec City in 1796. It stayed in a coffer in his attic until a young lawyer by the name of Louis de Gonzague Baillairge tracked down the flag after he investigated the story.

According to Brother Martinette, the flag had been flown during the Battle of Carillon, and Father Jean-Antoine Deperet carried the flag north during the evacuations of Forts Carillon and St. Frederic on Lake Champlain in 1759. The flag has a fleur-de-lis in each of the four corners, pointed inward, with the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child depicted above the Coat of Arms of Charles, Marquis de Beauharnois, the Governor of New France from 1726-1747. On the other side of the flag, the Coat of Arms of France is surrounded again by four fleur-de-lis in each corner, pointed inward.

Now, many historians doubt that this flag actually flew during the Battle of Carillon. Historian Alistair B. Fraser and others assert that the flag may never have been to Fort Carillon at all, and that the flag may have been at Fort St. Frederic, the other French Fort on Lake Champlain at present day Crown Point. Fort St. Frederic was built under the direction of Charles, Marquis de Beauharnois in 1734. Nevertheless, the association of the flag with the Battle of Carillon lived on in tradition.

In the early 1900's, in response to growing pressure (sometimes by force) to fly the Union Jack as the rest of Canada did, the French Canadians looked for a flag to call their own. In 1902, Abbot Ephège Filiatrault flew a flag in Saint-Hyacinthe that he called the Flag of Carillon. It had a fleur-de-lis in each corner, pointed inward just as the original Flag of Carillon did. The background was blue with a white cross. The following year, the Sacre-Coeur was added, surrounded by a wreath of maple leaves (pictured below). A campaign from the Society of Saint-Jean-Baptiste pushed for this flag to become the official Flag of Quebec. The Flag of Carillon was flown all over Quebec and even French communities in the United States as a symbol of French-Canadian pride.

Finally, in 1948, the Flag of Carillon was modified, with the fleur-de-lis centered and oriented upright in each quadrant of the flag. The Sacre-Coeur was removed as well. This flag, now known as the Fleurdelisé, became the official flag of Quebec.

Legacy: The Impact of the Loss of Lord Howe on the American Revolution

There’s one last item I wish to explore regarding the Battle of Carillon. That is the impact that the death of Lord Howe had. We shared the immediate impact, but it is interesting to think of the long-term impact. As stated earlier, Lord Howe had the respect and admiration amongst the colonials, and the feeling was mutual. The colonials loved him so much that the Colony of Massachusetts paid for a monument to Lord Howe at Westminster Abbey.

He was also a Lord back in England, where he demanded respect based on his social stature. Fast-forwarding to the Revolutionary War, could Lord Howe have possibly bridged the gap between the colonials and the lawmakers of the House of Commons? Looking back at the issues that led to revolution, those issues were actually pretty minor in the grand scheme of things. They were gentlemen's disagreements.

William Howe, George’s younger brother, commanded the British land forces from 1776 to 1778. He actually sympathized with the colonials, remembering the monument paid for by Massachusetts, and himself opposed the “Intolerable Acts” that inflamed animosity. He believed that he could negotiate peace with the colonials, however it’s unknown if parliament would have accepted any peace agreement had it been reached.

But heavy-handed policies towards the colonies escalated to rebellion. Could Lord Howe have bridged the gap? It is one of the more interesting “what if’s” from the colonial time period.

The Battle of Carillon thus lives in regard to the French and Canadians, while it lives in infamy for the British and Americans. It was an incredible victory, but 1759 would see the end of the French control of Lake Champlain.

This is Part 4 of a 6 part series on the French and Indian War. For Part 3 click here. For Part 5 click here.

Sources:

Anderson, Fred. “Crucible of War: The Seven Years War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766”

Bellico, Russell P. “Empires in the Mountains: French and Indian War Campaigns and Forts in the Lake Champlain, Lake George, and Hudson River Corridor”

Brumwell, Stephen. “White Devil: A True Story of War, Savagery, and Vengeance in Colonial America”

Cohen, Eliot A. “Conquered Into Liberty: Two Centuries of Battles Along the Great Warpath That Made the American Way of War”

Fraser, Alistair B. "The Flags of Canada" https://fraser.cc/FlagsCan/Provinces/Quebec.html

Millard, James P. “Lake Passages: A Journey Through the Centuries Volume I 1609-1909”